Struggling with Censorship in 1798

Perhaps the most important responsibility of government is to provide for the safety of its citizens. However, the means by which that security is acquired, and who enforces it, are tough questions in a nation that has ‘inalienable human rights’. Security and freedom are often at odds with each other.

Shortly after the American colonies won their independence from the British Empire, American politics had already been split into parties, despite the warnings against it from George Washington as he left the presidency.

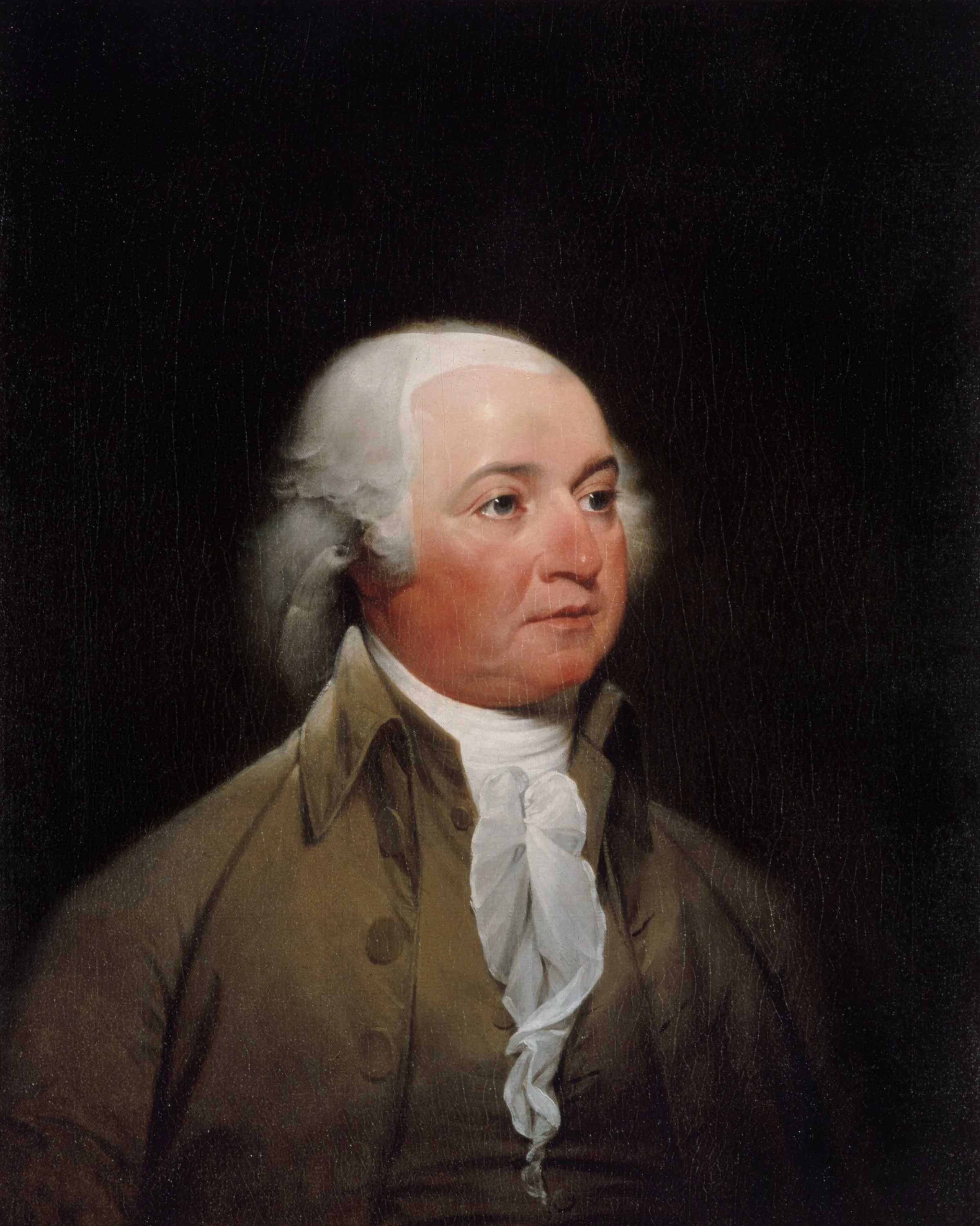

The official presidential portrait of John Adams, by John Trumbull. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The Federalist Party held generally conservative views and called for a strong national government that supported commerce and the rebuilding of a relationship with Great Britain. In 1798, they held sway in the nation’s capitol. John Adams led the party and sat as the 2nd president of the USA.

The Jeffersonian Republican Party, or the Democratic-Republican Party, opposed strong centralized control, and preferred to promote an agrarian vision for the future of America. Thomas Jefferson led this party, and was also vice president. At that time, the vice president was always the person who received the second-most support, rather than the president’s running mate.

Meanwhile, the Quasi-War with France had begun to simmer over.

Differing interpretations of past treaties, and discontent with American and Britain becoming trade partners again, led to French privateers beginning to attack American merchant ships. The Continental Navy had been sold off after the American Revolution ended, and America was unable to defend the shipping lanes. The French captured hundreds of ships, causing losses well into the millions of dollars.

Capture of the French Privateer Sandwich by armed Marines on the Sloop Sally, from the U.S. Frigate Constitution, Puerto Plata Harbor, Santo Domingo, 11 May 1800. Copy of painting by Philip Colprit. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

To defend their interests, the American federal government appointed Benjamin Stoddert as the first Secretary of the Navy in 1797, and approved limited use of force, rather than an all-out war with France. He was only to defend the shipping, not go on an offensive.

The Federalist Party-controlled government also passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which placed limits on immigration and speech.

The Sedition Act made false or malicious statements against the federal government a crime, which modern Supreme Court justices have said would surely be found to be a violation of the First Amendment were it to be challenged today. However, the Supreme Court didn’t have the authority to check such laws in 1798, and didn’t gain it until 1803.

Several prosecutions focused on writers who were merely critical of the administration of the day.

James Thomson Callendar wrote that President Adams was a “repulsive pedant”, among other things. He was indicted, convicted, sentenced to nine months in jail, and fined $200 (almost $5,000 today, when adjusted for inflation).

Vermont State House portrait of Matthew Lyon. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Matthew Lyon was a U.S. congress member representing Vermont. A part of the Jeffersonian Republicans, he published letters critical of sitting President John Adams, the leader of the political party he opposed. He was charged, fined $1,000, and spent four months in jail. While he was in jail, his supporters threatened to raze the building to free him, but he urged them to be peaceful. He won reelection to his seat while still imprisoned and returned to Congress on his release.

Two newspaper producers, Benjamin Franklin Bache and Anthony Haswell, were both charged under the sedition act for things published in their newspapers. Bache died of yellow fever before his trial. Haswell was fined $200 and spent two months in jail, for doing little different from what people do on social media every day in 2023.

A man named Luther Baldwin was convicted and fined $100 for an incident during a visit by President Adams to New Jersey. Baldwin was drunk, and on hearing a gun report, shouted “I hope it hit Adams in the arse!”

“I hope it hit Adams in the arse!”

The most severe sentence was handed down to David Brown, the leader of a group who set up a liberty pole with the words, “No Stamp Act, No Sedition Act, No Alien Bills, No Land Tax, downfall to the Tyrants of America; peace and retirement to the President; Long Live the Vice President.”

Brown was fined $480 and sentenced to 18 months in prison after refusing to name the others in his group.

These Acts, and the actions based on them, were widely unpopular, especially with those who held to Jefferson’s points of view about agrarianism, individuality, and independence. In some states, there was even talk of succession over these violations of free speech.

Ultimately, the Alien and Sedition Acts contributed to the Federalists losing a close election in 1800, giving the Jeffersonians the power to let the Alien Friends and Sedition Acts expire.

However, the Alien Enemies Act remained in effect, and was used in 1941 to apprehend and deport Japanese, German, and Italian non-citizens when the US joined WWII.

The First Amendment, and the rest of the Bill of Rights, are powerful documents, but they have no power in a vacuum. Without empowered courts and invested voters, even short-lived administrations have a powerful ability to sway, or chill, the public conversation.