The Stamp That Never Was

Great Britain had a debt problem.

They had secured victory in the Seven Years’ War at the beginning of 1763, but had incurred a huge expense. The London-based Parliament figured it was justified in taxing their various colonies to pay their debts, since the expense incurred was to defend the citizens therein from French and Spanish incursion.

The issue being that the American colonies had also been spending their own money and incurring their own debts to prepare for and fund their own part of the war.

To make matters worse, when Parliament decided on their new tax, they chose to tax all printed material with the Stamp Act. The act required publishers to use special paper that had a special stamp, bought for a fee from government-appointed stamp sellers. They passed the legislation in March 1765, and it was to take effect the following November.

The Board of Stamps prepared two hundred copper dies and eight plates of the one-penny stamps. Dark red proof impressions of the plates were made on thick laid paper before production of the stamped paper began. Only thirty-two copies of the original dark-red proof impressions made in 1765 have survived. Via WikiMedia Commons.

Fees would be levied on playing cards and pamphlets, and taxes on lawyers and college students would limit the growth of the professional classes. Even worse, the language of the law contained wording about courts with ecclesiastical jurisdiction. Many colonists had fled Europe to avoid such state-sanctioned religion.

This tax would be especially costly for newspapers. The tax would be one penny per sheet on newspapers. That’s 41 cents adjusted for inflation, per sheet. For a business that relied on being able to publish many copies at a cheap cost, this was a death sentence.

The writers of the day didn’t agree on much, but they agreed that the Stamp Act had to go. Across the colonies, essays, columns, and letters decried the evils of the Stamp Act.

The Boston Gazette let loose a salvo signed only ‘B.W.’, though many suspect it may have been penned by Samuel Adams, who spent much of his time at the publishing office.

“The Love of Liberty is natural to our Species and interwoven with the human Frame. Inflamed with this Love, do not countenance an Act so detrimental to your Privileges…”

—Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal, October 7, 1765

Other writers, like this anonymous one who wrote to the New-York Mercury, spoke with anger toward those who would enact the law.

“Think not, whoever you are, that have been instrumental in ruining your country, that you will escape with impunity.—Misery, even in this life, shall be your portion.—The present generation shall never mention your names, but with succeeding ages, inform’d by the faithful historian, to whom they owe their shackles, shall load your accursed memory with everlasting infamy.”

—New-York Mercury, October 21, 1765

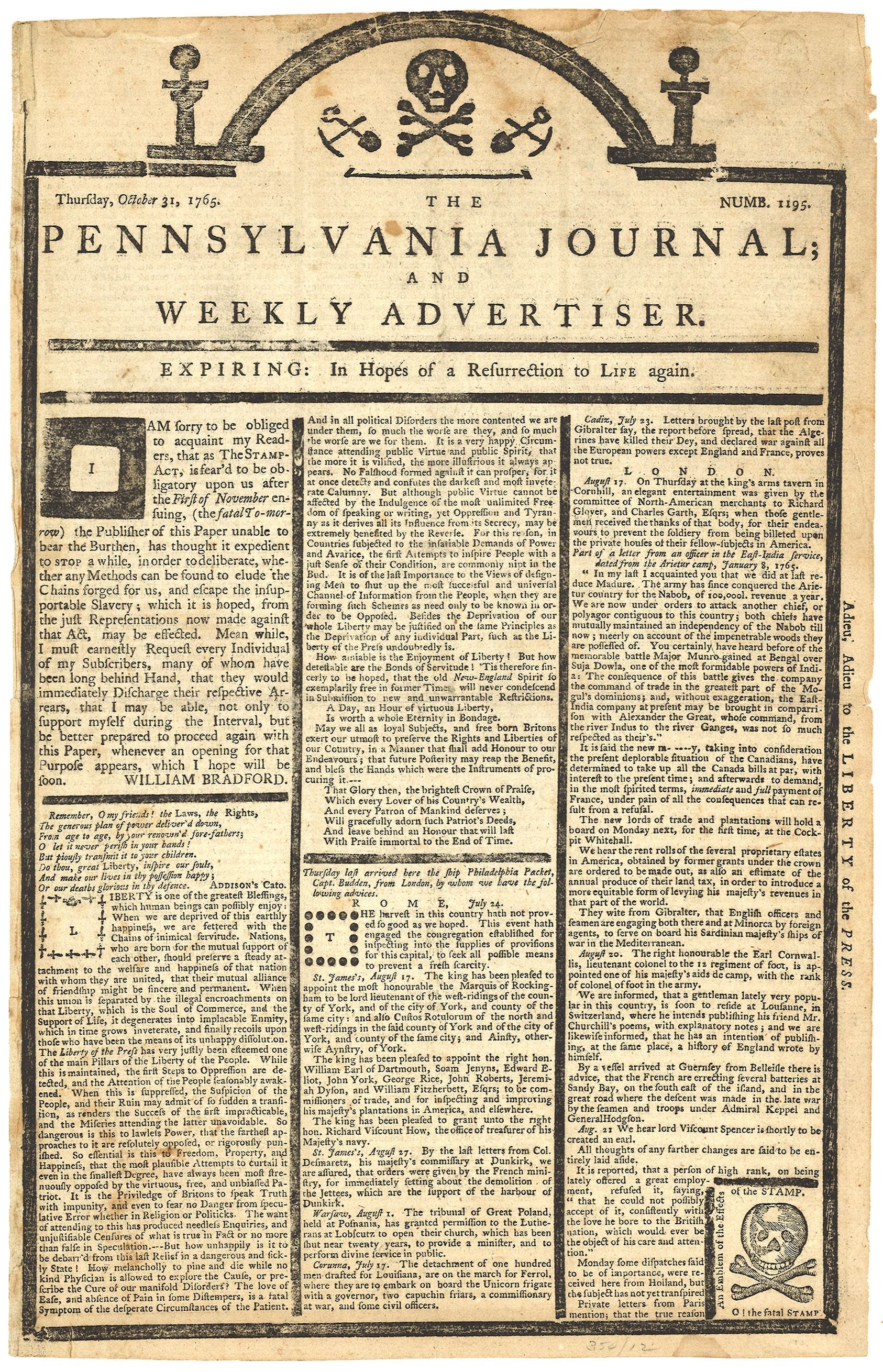

The day before the Act was to take effect, William Bradford of the Pennsylvania Journal changed his masthead to make the paper look like a gravestone.

“EXPIRING: In Hopes of a Resurrection to Life again.”

“I am sorry to be obliged to acquaint my readers, that, as the Stamp act is feared to be obligatory upon us after the First of November evening, (the fatal To-morrow,) the Publisher, unable to bear the Burthen[sic], has thought it expedient to Stop awhile, in order to deliberate, whether any methods can be found to elude the chains forged for us, and escape the insupportable Slavery; which, it is hoped, from the just representations now made against this Act, may be effected.”

—Pennsylvania Journal; and Weekly Advertiser, October 31, 1765

In the lower-right corner of the newspaper, where the official stamp would be required, he placed a skull and crossbones.

“An Emblem of the Effects of the STAMP.”

Many papers suspended publishing at the beginning of November, but shortly began publishing again, with no stamp. Some of them noted that they couldn’t find any stamped paper, even if they had wanted to purchase it.

As November 1 had approached, the vehement opposition to the Stamp Act had intensified, and the stamp sellers who lived in the colonies had all resigned. Some were forced. Some were tarred and feathered. Finally, in March 1766, the British Parliament repealed the Stamp Act as unenforceable.

However, the British Empire had made a fatal mistake. In alienating the colonists, those colonists began thinking of themselves as Americans rather than as Englishmen. A unified voice had been given to the newspapers. Samuel Adams founded the Sons of Liberty in the summer of 1765, and would continue to work to drive a rift between the colonies and Great Britain through the American Revolution.

Thanks to the Stamp Act, America had gained a national identity.